By: Tomas Bernales-Jabur

Madame. A title that exudes the elegance and pragmatism of a teacher who is respected throughout the Rudolf Steiner School community. Few students and even teachers, refer to her by her full title, Madame Sergeyeva, simply saying, Madame. This moniker resembles something out of a novel set in France in the 19th or 18th centuries. In fact, Julia Sergeyeva’s life could be mistaken for a thrilling novel, with her early life set in the Cold War-Era Soviet Union, eventually leading a successful career in New York City.

Julia Sergeyeva was born in the outskirts of Moscow, to a French mother and Ukrainian father. She grew up among a mix of languages: her French-speaking mother taught German, and her father spoke Russian. Her father fought in the Soviet Army from 1940-1945, marching from Latvia to Berlin. When I spoke to Madame between her classes, she mentioned pictures of her father on the steps of the Reichstag in May 1945.

Growing up, Madame’s mother sang her French songs and read her French fairytales by Charles Perrault. Madame could speak French and enrolled at the Lycée Français in Moscow where she spent her early years of education. Graduating from the Lycée, Madame entered the Foreign Languages University Maurice Thorez, receiving a bachelors and masters in French and pedagogy.

In keeping with her pragmatic reputation, Madame wasted no time after receiving her degrees. Inspired by her mother, she began teaching French at the foreign language courses in the Moscow City Hall, where she subsequently became the senior teacher. She would continue teaching here from 1973 through 1991. When speaking to Madame, she reminded me, that despite the Soviet Union being isolated from the Western world, European languages were valued in populated Soviet cities like Moscow, where intellectual vitality and education were respected.

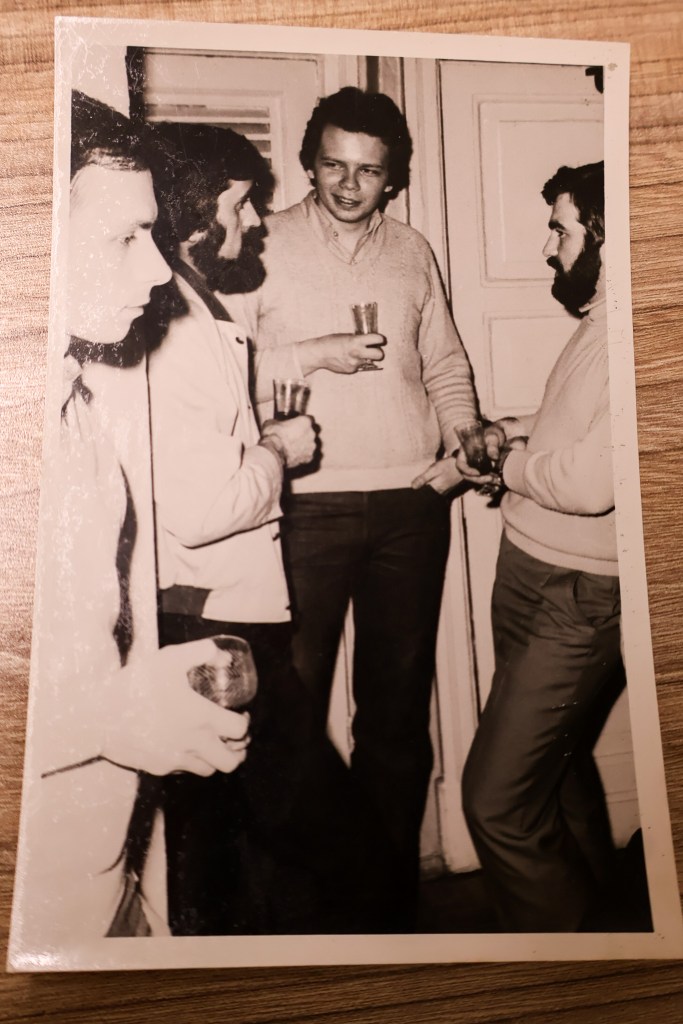

Teaching languages, Madame met a wide variety of people, from different ages, backgrounds, and professions. She taught sixteen to sixty-five year olds, some were doctors traveling to Algeria or Morrocco or flight attendants learning French because they received a greater salary from Aeroflot if they flew international. Other students included a biking champion, a fencing official, a successful IBM technician, and Elena Sharnova, a art curator in the Pushkin Museum. Madame also remembers being told, by one of her students, to “stop speaking of politics as [she] did.” Madame would incorporate ideas of politics and culture into here lessons, and the student warned her the government did not approve. The student was employed by the KGB.

With the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, Soviet officials asked language teachers to start preparing team bus drivers. Madame participated in this preparation, which began in 1978. She recalls these drivers were all selected from the provincial towns and were all party members. The classrooms were packed with thirty men, reeking of tobacco, “sitting quietly like little children.” “Outside the class they were rude guys,” Madame says, “but in the classroom they were polite and humble.” Year later, she was walking on the street, and a large commuter bus honked at her, and she heard her name called out. A smile crept onto her face when she told me it was a former student, remembering her after all those years.

After teaching the drivers, however, her work for the Olympics was not over. She was assigned to the boxing events as an interpreter. Because of the violence and gruesome aspects of boxing, Madame asked to be switched to a different sport. “The blood and violence is not for me,” she says. They re-assigned her to diving, where she acted as an interpreter for the doctors. Wonder crept into her voice, as she described the magnificence of sitting on the edge of the diving pool and seeing the divers plummeting from ten, seven and five meters. She then remembers going a few levels below and seeing, through a glass panel, as they slowed underwater.

Throughout her tenure at the Moscow City Hall language courses, Madame also held many parallel, part-time jobs. In 1977, she worked as a private interpreter to Robert-Jean Longuet, a French lawyer and journalist and the great-grandson of Karl Marx. She also taught the curators at the Moscow History Museum on the Red Square. Furthermore, when Michel Legrand’s musical “The Count of Monte-Cristo” was produced at the Moscow Theater of Operetta, Madame acted as a French tutor and rehearsed with soloists and chorus on their parts.

In 1991, with the end of the Cold War, and for a variety of reasons, Madame moved to New York City. An aunt of hers lived in New York, and her son dreamed of living in the city. Madame also describes a “suffocating environment” in the Soviet Union. When she arrived in New York, she was in a hurry to find a job and began handing out CV’s in several places. In February of 1992, she walked into the Rudolf Steiner Upper School, never having heard of Waldorf education, and handed in her CV. September of that same year, she began teaching French at our school.

Along with the German teacher at that time, Frau Gudrun Hahn, Madame created and developed the structure of language education we are familiar with today. They created the different levels and established the language exchange program. According to Madame, the exchange program began only for French and German speaking countries, with Spanish speaking countries being added eventually. Madame emphasizes how important she believes the exchange programs are, providing students a glimpse into different cultures and widening their horizons.

Throughout her life Madame has held many different jobs, from interpreting, to translating. Nevertheless, she insists her love and vocation is teaching. Language lessons allow her to bring to her students not only the knowledge of a new language but a love for France, French culture, history, traditions, arts, music, and politics. As many students can testify, one of Madame’s favorite ways of teaching are individual lessons. “I have been always cherishing [the] individual approach to teaching French to students [who have] different level of knowledge of French, different characters and backgrounds,” says Madame.

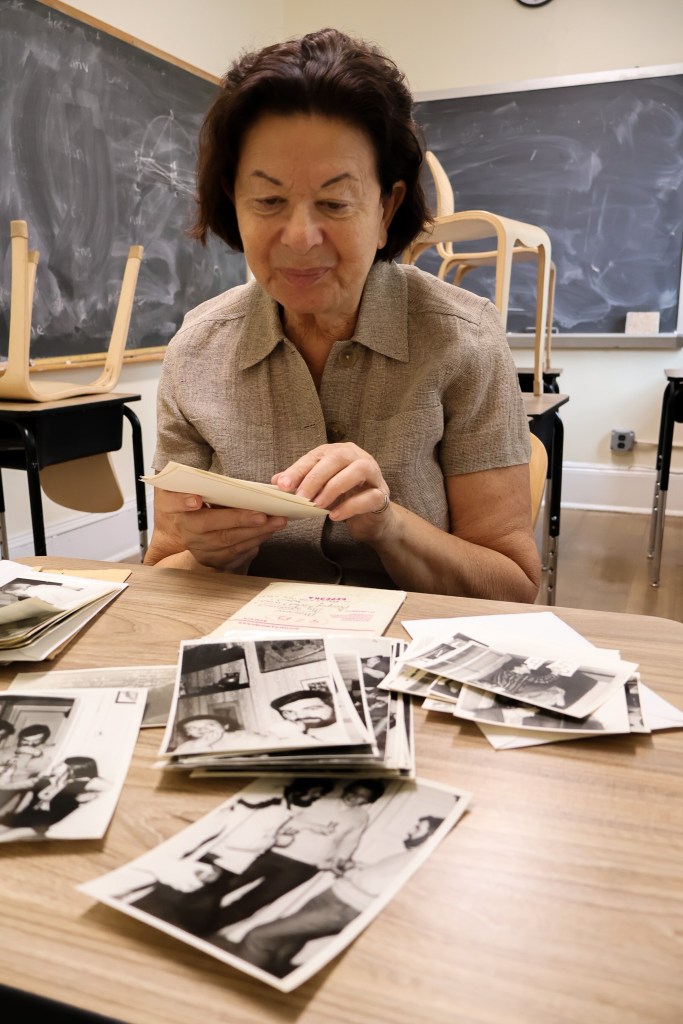

Through her love for teaching French, Madame has met many different people. Recounting her story to me, in an airy and well-lit room in the Rudolf Steiner School, she would lapse into occasional silences, as her mind drifted in the past, remembering the people she had taught. One thing that became clear from her descriptions of her students, is the immense respect they have for her. Madame’s dedication to improving our French and helping us attain a fluency and deep knowledge of French culture is admirable.

Indeed, it is this passion for improving her student’s French, regardless of their background, characters, and willingness, which has brought life to so many of these stories. Madame’s life is an example of how language transcends barriers, both political and social. She met people of all walks of life, yet they were all united by language. Her dedication to French is also what opened the avenues for opportunities that created many of these stories. And for the past three decades, Madame has brought this passion for teaching and dedication to the French language, to the Rudolf Steiner High School. `