By: Annie Plane

I had been looking forward to tenth-grade exchange for at least five years when I arrived in Buenos Aires this August. I had no idea what to expect. The questions I got from my friends and family during and after my exchange are indicative of the general knowledge I had about Argentina going in. Do they drink mate? More than water. Do they eat a lot of steak? Yes. Dulce de leche? Yes. Am I pronouncing that right? No.

All of my own questions had to be answered through trial and error once I landed in Buenos Aires. I couldn’t have done any of it without the Bartoli-Espiñeiras.

I’m extremely lucky to have had a wonderful and vibrant exchange family. My exchange’s name is Andrea, she’s 16 and loves reading and 2014 tumbler girl fashion. Her mother is also named Andrea, she’s a lawyer and a health nut. Her father, Christian, is very serious and loves Depeche Mode. Her brother Pedro loves soccer, her other brother Fransisco loves Charly Garcia. Her grandfather, Andres, loves tango music and orange soda.

Though I had many cultural missteps during my exchange, I did try to research as much about Argentine culture, music, history, geography, and politics as I could before I arrived. Most media was dominated by the current economic crisis, which in many ways framed my experience of exchange. Even though the private school community I was in wasn’t hit the hardest, everyone felt significant stress.

Our inflation looks trivial compared to Argentina’s, which peaked after the pandemic at 292.2% annual inflation (April 2024). US inflation never got above 9.1% (June 2022).

The Bartoli Espiñiera’s told me about how when they visited California in 2018, Andrea dropped and broke her phone. They planned to go buy a new one the next day (crazy high import taxes mean that foreign products are super expensive in Argentina, for example when I broke my phone charger [for the first of four times, no I don’t want to talk about it] and went to go buy a new one, an official apple charger would have cost the equivalent of $67, so I went with off brand). The exchange rate of pesos to dollars at the time was around 60:1. The next morning when they woke up to go to the apple store, the rate had jumped to 80:1 overnight. They did not end up buying a phone that trip.

Even worse, the exchange rate 8 years later is around 1,012:1

To put that in perspective, if you inherited 1,000,000.00 Argentine pesos in January of 2018, it would have valued around $27,000 US. If you left that amount completely untouched in a bank or shoebox or under the mattress (and we ignore taxes for a little bit), at the time of writing it would only be worth $997. Thats why when Argentines do save money in a bank, or shoe box, or under the mattress, they do it in Dollars (or Yuan, or Euros. Pretty much anything is better than the peso).

Though the newest presidential administration, under “Anarcho-Capitalist” Javier Milei (who would need his own article to fully explain) is loosening up taxes on imports and generally liberalizing the national economy, most production of goods and services remain domestic. While things like food are quite affordable, because of these trade policies, they lack a diversity of choice that most Americans take for granted. Other goods, especially clothing, are actually just as or more expensive than you might expect to find in the US, despite a comparatively much lower median Houshold income. This is because Argentina has maintained very strict regulations on labor, pay, and working hours since the rise of the the pro-labor, leftist-populist Peronist party in the 1940s.

One of the most ubiquitous things in Argentina is its national pride and identity. While in the US, a hyphenated sort of ethno-national identity is widely accepted (e.g. Italian American, Mexican American, Irish American, African American), the same is not the case in Argentina. I did not meet a single person there that, when talking about their family (many of whom were first or second generation in the country) as anything but Argentine. This may be because Spain and Italy alone make up the vast majority of Argentina’s 97% European-descended population, meaning it is a less diverse place then the United States. Another reason could have to do with a legal principle, jus soli and jus sanguinis. Andrea’s mother, a lawyer, brought up this concept after an animated discussion of Madonna, but it means “right of soil, right of blood, “where you were born or where your family is from. It’s used to determine citizenship status but has cultural relevance in that most Ango-Saxon countries implement blood-right citizenship while roman origin countries have birthright citizenship. Notably, both the US and Argentina use a hybrid model, but culturally view the concept of citizenship and identity very differently. This is just another example of what it means for something or someone to be “made in Argentina.” For my part, anyone who uses Fahrenheit is an American.

While all Argentines are extremely patriotic, those that attend so called “German Schools” step into another facet of national identity.

The Colegio Rudolf Steiner, the school I attended for three months on exchange, identifies itself first as a German school and then as a Waldorf school. More importance is certainly placed on German than English, but there are more German classes a week than math or language arts.

All the other exchange students at the school, at least while I was there, were German, which I was excited about, as most Germans speak good English (my excuse for not trying very hard in German class). Most people at the school, seeing me in all my WASPy glory, assumed I was German and would speak to me in German, even after learning I was American. They just forgot, but it was funny every time.

“Ich mag deinen Pullover,” one girl said to me, about two months after I arived.

“Danke.”

Because despite the fact that I’m blonde and pasty, i do not actually speak German. This was about how my first German class went.

“Ich nicht spreche Deutch.”

“Du sprichst kein Deutch.”

“Exactly.”

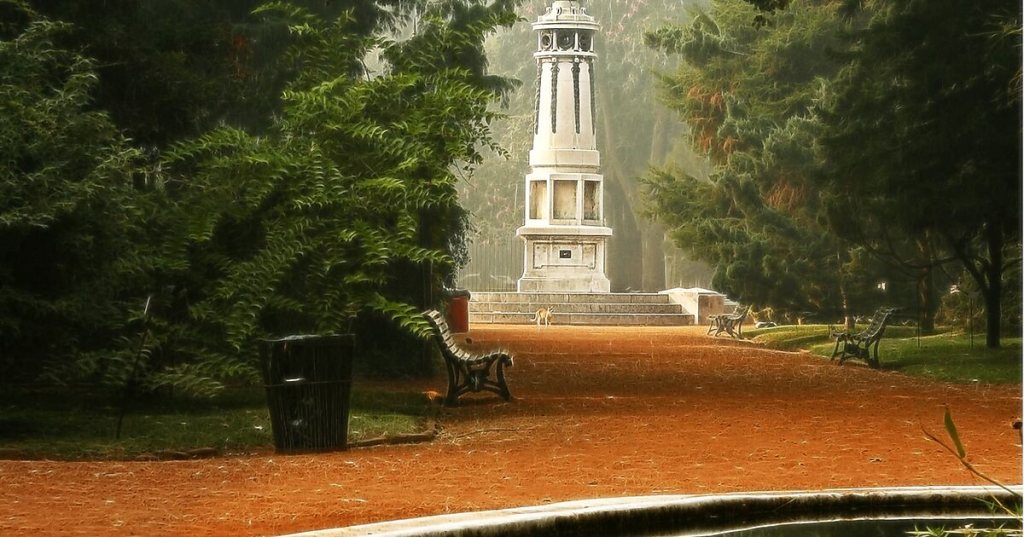

One of the first times I really saw this “German School” idea in action was on German re-unification day. Celebrated the third of October, German Unity Day celebrates the date almost a year after the fall of the berlin wall when East and West Germany were officially unified as one country for the first time since WW2. The German schools in Buenos Aires all gathered in the Plaza Alemania under the scorching sun, carrying large flags and banners, and many with little children clad in lederhosen. The whole square was decked out in German imagery, and a marching band came to play the German and Argentine national anthems. Though, to be fair, the Argentines stuck to their guns and the whole affair ended in a round of Alfajores for everyone.

I think, besides the people, miss Argentine sweets the most. The most popular is the Alfajor, two cookies with dulce de leche in between, dipped in chocolate. A close second is ice cream, which is worlds better than anything in this hemisphere.

Last Friday night before I left the country, before we went out to get ice cream, I heard voices and stepped out into the backyard. It was a starry night, even though we couldn’t see it. As in New York city, the light pollution blocks out the stars.

On one of my first trips into the city, we went to the planetarium and watched a projection of the night sky from the ceiling. There are some constellations in the southern hemisphere, and it was a strangely out-of-body experience, to see the constancy of the sky so changed. I think I am different now, having seen the stars on the other side of the world. I looked out into the vast, mystery of the universe, with land under my feet that was equally as foreign.

So, I knew the stars were there, even if I couldn’t see them. That night, it was Andrea’s mother, Andrea, and her father, Andres, in the garden. He was my favorite. Andrea went inside and I sat next to him, staring up at the starless sky. Andres pointed towards a hanging plant, softly illuminated by the light of the windows.

“Look, the shadow of the plant, it looks like an old man drinking mate.”

It did, all be it and old man with very skinny legs.

“So, Andres,” I said, “when I go back, what do you want me to tell the Yankees about Argentina?”

He ranged from very serious to quite silly at times, so I didn’t know exactly what to expect.

“Tell them about la Amistad.”

At the time I misunderstood him, I thought he meant peace, or armistice, I now know that Amistad is the practice of friendliness, openness, and affection between people. But for what he said next, it could be taken the same either way.

“You know, we’re a poor country. Today we might not have anything to eat, but we can still share a mate. You still smile at strangers. If you’re on the bus and a pregnant woman gets on, you give up your seat. I can’t walk anymore (he used a walker) but when I go to a museum, everyone wants to help me; they hold the door, they go find me a wheelchair. It’s basic human decency, we respect each other.”

Andrea had said something similar when I asked her the same question.

“Just tell them how friendly we are.”

As far as international exchanges go, I don’t think I could have chosen a more open and welcoming place. It was hard to be in a new country where I didn’t know anyone, five thousand miles from home, but I found people there who now feel like missing parts of my life. To be the only foreigner in the room would have unnerved me in any other place.

I for one, enjoyed the peace. I came for Argentina because I wanted a completely different experience, an adventure, and a chance to be alone, in some sense.

I think I am better for it. I found myself on the other side of the world, and even thought I had to leave, I think a part of me will stay in Argentina, at least for a little while. I’ll have to go back and find it one day.